Why The Skeptical Movement Is Not Changing The World

Louigi Verona

November 2017

An introduction from 2023:

When I published this article in 2017 and began showing it to other skeptics, I was surprised that it did not initiate what I believed was an important conversation about skeptical activism. Instead, my analysis was mostly greeted with indifference and sometimes bitter disagreement. Disappointed, I myself then bitterly concluded that skeptics are not thinking critically when it concerns them. But while it's always more difficult to think critically when one's skin is in the game, I don't think this was necessarily the case here.

Having re-read this article today, in 2023, I still think that it's a very important piece of analysis. However, I also have a hypothesis as to why it had no impact: it was the lack of credibility. Credibility that I had, but did not put to good use.

I have this tendency to write critical analyses with a voice of an external observer. It's mostly a stylistic choice, but the problem here is that even at the time very few people in the international skeptical movement knew who I was. And I think to many folks this looked like one of those articles written by someone who knows nothing about actually doing the work, and just criticizes those who do.

At some point I even write "The author of this article had the honor of providing personal feedback to two skeptical podcast teams", which comes off exactly as what someone from the outside would say. It doesn't take much to provide "personal feedback" to podcasters. What, did I write them a comment on YouTube? Innundated them with emails?

But, of course, the context here was very different. And I failed to take into account what my potential audience would need to know to appreciate my message.

For instance, nowhere in the article do I explain that I myself have founded a skeptical organization, an organization started completely from scratch and then grown into an international body, operating across three countries.

Nowhere do I explain that I myself ran a podcast - the first skeptical podcast in the region - and that I ran it for 1.5 years producing 70 weekly episodes, mentoring a team of several rotating co-hosts and personally spending around 16 working hours per week producing each episode. I had no concept of a weekend during that time.

And also that one of the teams I was providing feedback to was the team that essentially took over my podcast after I had left and asked me for feedback. Another team also proactively reached out and requested feedback.

At some point in the article I talk about how difficult it is to get a critical thinking program be officially accepted by a school or a college committee. I don't point out that members of my organization had actually tried it, and I am speaking from first-hand experience. In our case, the program was about to be accepted by a private college when one of the committe members identified part of the program that clashed with their personal beliefs and rejected the whole initiative.

And I think this really hurt the impact of my essay. Instead of explaining that it is coming from an experienced skeptical activist, I made the analysis sound impersonal and detached.

And my story is actually a story of someone who was extremely passionate about being a skeptical activist. Raised in a fairly religious family that fell into the New Age trap, my path to skepticism was a rare one. I went from being maximally religious to a pro-science critical thinker. This also positioned me well to lead a skeptical organization because of my experiential empathy. I knew how it felt. I knew that folks "on the other side" are not stupid or crazy. And in the toxic atheist and pro-science community this empathetic approach was deeply innovative.

I founded and ran the organization for 2 years. We've helped many people. I've had people tell me that my podcast was one of the main reasons they left a cult. You don't hear that everyday. You don't normally get to have that kind of impact on someone's life.

And helping real people feels intoxicating. Empowering. Makes you feel like you are a part of something that's much bigger than yourself. In many ways, I still feel empty. I still don't know what to do with my life, because I tried the forbidden fruit of doing work that went far beyond my private world. It's very tough to no longer be part of that.

But there is also a bubble effect. As you grow your organization, you can't help but compare yourself to other activists. You want to make sure you've got everything that the more established organizations have... You are part of this microcosm of skeptical activists, and you begin to assess the impact of your work in this internal context. The shift is subtle and usually goes completely unnoticed.

And then I had to leave the country and this placed me out of the bubble. I knew that I couldn't run the organization from abroad, nor did I want to.

And as I began to drift away, I was taken aback when I realized that outside of our cozy skeptical subculture the larger world knows very little about it. That our skeptical celebrities are no longer relevant. That the public had long forgotten even our heavy hitters. It was 2016-2017, and by that time James Randi was perhaps still somewhat known among magicians, maybe in some adjacent science communities, but his name was long out of public consciousness. Michael Shermer who appeared on TV in the 90s and early 2000s was in that sense also out of commission.

It was even worse when it came to the skeptical message. The world around me knew virtually nothing about even the basic concepts. "Falsifiability? What's that?" "Scientific skepticism? Do you mean you are skeptical of science?"

And so this article was first and foremost the record of my own revelation. It was also a significant disappointment. I felt betrayed. Embarrassed even. I thought the work I was doing was important. And it was! Just not as important as I made it out to be.

In 2017 I went to Poland for the European Skeptical Congress. But by this time I was quite disillusioned by the whole thing and my only goal was to see Randi again. I suspected it would be the last time. I wanted to ask him about one of his tricks, too. It was a memorable event for me, but I didn't pose for the photo because I didn't care for the skeptical activism part anymore. It all seemed pointless. When Randi passed away, I did regret not seeing myself in the participants photo. Although I do have photo and video evidence I was there, of course :)

And it was during that trip that I had decided to write this analysis. I wish I had made it more personal. I don't know if my hypothesis is correct and if people would've cared more.

But I can tell you this. This article is as much about me as it is about other activists. I didn't see any of this when I was engaged in skeptical activism. I prioritized content that was oriented towards ourselves just like many other skeptical groups do today. I was under the illussion that my activities had the chance to visibly change the world.

And hey - that's alright. Not everything needs to be this grand mission to rewire society. But when I stopped being religious, I was grateful that I no longer have that veil over my eyes. I was as grateful when I did not have this one. Disappointed, but grateful. It's fine if the skeptical movement is not changing the world - as long as this is a conscious decision. And in my case it wasn't.

Louigi Verona

August 2023

Skeptical activism, just like any other activism, pursues two main goals:

- Build and maintain a community of like-minded people

- Change the world in accordance with the views of the group

The first goal is a necessary step for any effective activism. The attempts to reach the second goal is actual activism.

The claim of this article is that the modern skeptical movement, originated in the 70s of the 20th century,[1] is doing a satisfactory job at maintaining a robust community of skeptics and science communication enthusiasts, but has an extremely poor record at activism, almost no tangible results after over 40 years of skeptical initiatives, as well as a strategy so vague, that it would not be wrong to call it non-existent.

At the same time, I am not at all claiming that skeptical movement as it exists today is useless, since I believe that creating a vibrant community of like-minded people is already adding considerable value to the world.

I will start off by noting that activist groups that have managed to change the world are numerous. Environmentalist groups, such as Greenpeace and World Wildlife Fund are examples that immediately come to mind. While generating their fair share of controversy, these projects have visibly changed the way our societies operate daily. Electronic Frontier Foundation is another example of an activist organization that fights for their vision of privacy in the digital world and has considerably changed the legal landscape both in the US and in Europe. Obviously, the list of successful activist groups is very long and I have picked these as random examples.

Skeptic groups, however, might find it more difficult to boast such results. Most of the activities of the movement remain to be ineffective at achieving real change. For instance, the author of this article knows of only a few regulations that have been passed because of a skeptical group activity. That no results of such magnitude exist can be readily seen even if one compares the list of activities of such notable skeptical organizations as CSI (CSICOP)[2] and Skeptics Society[3] with a list of activities of the above-mentioned WWF, Greenpeace or EFF. The focus of skeptical groups seems to mainly be the communication of skeptical commentary to the media, as well as numerous skeptically-themed events and media content, which are tailored to the like-minded, but do very little to produce change.

For anyone intimately acquainted with the inner workings of the skeptical movement this conclusion should not be surprising. The current state of affairs is explained by relatively transparent reasons. Let's take a more detailed look at these reasons.

1. The audience of a skeptical organization

An analysis of activities of many skeptical groups uncovers a pattern of allocating significant resources to the production of media content and events geared towards those who are already aware of what scientific skepticism is and why it is important.

Numerous annual conventions are capable of filling up the schedule of a skeptical activist and taking her all over the world to gatherings of like-minded people. Speakers at those events would largely be covering advanced topics, topics that would be uninteresting or even unclear to anyone who is not already well-informed about scientific skepticism. Events where non-skeptics would be present are extremely rare, and usually they would be a representative of an opposing side, like a professed psychic or a professional creationist debater, not someone from the general public.

The outreach of such events outside the skeptical community seems to be negligible. Arguably the biggest and most successful skeptical conference The Amazing Meeting, that ran from 2003 to 2015, has an official YouTube channel.[4] A quick browse through channel statistics allows to formulate a plausible hypothesis that the channel is mostly viewed by skeptics themselves. For example, a TAM 2014 playlist shows that most talks and panel discussions have well under 30k views, the keynote with Bill Nye has slightly under 115k views, the Million Dollar Challenge has under 172k views - in context of digital media these are all very low numbers.

While there are exceptions, in particular when videos involve celebrities, the amount of views rarely exceeds 30k for other videos as well. For instance, a more popular video of a Penn and Teller interview (TAM 2012, half a million views) is followed by talks from the same event, all of which have under 30k views. The 2012 Million Dollar Challenge video is an exception and has 271k views.

Media content produced by skeptical organizations is of similar character. Most podcasts would make sense only to skeptics themselves, and, perhaps, to people they are criticizing. The author of this article had the honor of providing personal feedback to two skeptical podcast teams, and in both cases one of the points was that these podcasts are too cryptic for someone outside of the community, with heavy use of terminology that would be unfamiliar to a non-skeptic, and a dense stream of references to names, events and media that would be considered quite obscure by the general public.

One of the super stars of the skeptical movement is the podcast "The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe". What this podcast does notably well is add value to people who are already skeptics. SGU hosts provide a lot of insightful information about science news, as well as informed opinions on various publications and events of the skeptical community itself, including the discussion of supernatural claims.

The listenership of SGU is difficult to evaluate. In 2014 a number of 80k listeners had been thrown around, however I could find no evidence to corroborate this claim. As of the moment of writing, the Facebook page of SGU counts over a million likes, which is not an insignificant number, although Facebook likes are not always reliable at reflecting real people.[5] It is possible that the podcast also attracts people who generally like science. To compare with similar science communication projects, "I Fucking Love Science" has 25+ million likes, "Veritasium" has 370k likes, his main channel being YouTube with over 4 million subscribers and an average amount of video views at around 1 million. So, SGU definitely seems to attract a numerous audience, but it is not clear how big this audience is. It is also probably an audience of like-minded people, not the more general public. The podcast itself is definitely geared towards people who understand and agree with the scientific-skeptical approach, and would be difficult to follow for someone who is not acquainted with the general context. It is probably a good vehicle for helping scientists and science enthusiasts to begin to self-identify as skeptics.

In the 90s James Randi hosted a TV program called "Psychic Investigator".[6] The show had 6 episodes and was an example of a skeptical program that could appeal to the general audience. A number of other programs, such as "Mythbusters" and "Penn & Teller: Bullshit!" were created to communicate the skeptical approach without requiring the audience to know what scientific skepticism is. They however, were not the initiative or production of any of the skeptical organizations. As of the moment of writing, I know of no program with a wide viewership initiated by skeptical activists that would appeal to the general audience.

Therefore, as far as events and media content is concerned, skeptical groups seem to be generally addressing their own community, and show little interest to engage with the general population. It is, of course, obvious that a relatively small amount of people might be drawn into skepticism as a result of being exposed to this skeptics-focused content, but some of the statistics outlined above guarantee this number to be in most cases insignificant.

It is clear that the skeptical movement is relatively good at maintaining a robust internal life, consisting of media content and events for the like-minded. But what can be said of the skeptical influence on the outside world?

This influence, although not nil, is mostly imperceptible. The reason for this is that most skeptical activists stop short of doing actual activism. Examples of this are abundant, and I will take a look at a few situations when expected action from skeptic organizations failed to materialize.

Obviously, isolated cases exist, and include work like the Anti-Superstition and Black Magic Act in India,[14] or the activities of the Good Thinking Society in the UK.[15] But, as of the moment of writing, these examples seem to be exceptions rather than the rule.

2.1 Critical thinking in public schools

One of the most frequent sentiments expressed in the skeptical movement is that critical thinking should be taught in schools. Interestingly enough, there hasn't been any significant concentrated effort in this direction. If the foundation of CSICOP in 1976 is to be taken as the beginning of the modern skeptical movement, 40 years later none of the skeptical organizations have actually proposed a sensible school and/or college critical thinking curriculum. Although the installment of such a subject in schools could have lasting effects on the society, skeptical organizations have not to my knowledge created an educational program that would be suitable for schools.

Efforts that do exist are mostly of an isolated nature. Notable examples include Steven Novella's critical thinking course entitled "Your Deceptive Mind: A Scientific Guide to Critical Thinking Skills" at The Great Courses, a resource produced by the Teaching Company. Michael Shermer's course "Skepticism 101: How to Think like a Scientist" is carried by the same distributor. The Skeptics Society, led by Shermer, offers what they call "The Skeptical Studies Curriculum Resource Center". It is described as "a comprehensive, free repository of resources for teaching students how to think skeptically." However, it is more akin to a collection of books, essays and other educational information, rather than being a school-oriented program.

But the difference between an online course and an educational program prepared for public school usage should not be underrated. While I am aware of no initiative coming from the bigger skeptical organizations, I am well aware of local attempts at integrating critical thinking into public education. Creating a curriculum as in "a progressive educational program" is not that difficult. What's difficult is authoring a curriculum that could in practice be accepted by a school or a college. Small-scale attempts made by individual activists demonstrate that there are many caveats to the process, with committees objecting to all sorts of things in the program, from not wanting to create controversies on politicized topics, to being believers in certain pseudoscience themselves. The work of creating an agreeable program is enormous, and would require years of expertise, lobbying and failed attempts in order to finally succeed.

This work, however, is yet to be undertaken by the skeptical movement. In a number of countries religious groups have been markedly more active and, as a consequence, more successful at squeezing their agenda into the public school system. This is so far a battle not only profoundly lost by the skeptics, it is a battle which skeptics feel they don't need to attend.

The general absence of lobbying and litigation efforts has led to there being no infrastructure built for such action within the skeptical movement, even in democratic countries, where activism is a strong method of introducing change. This, in turn, leads to a situation when all skeptics can do is complain about court decisions, laws and other political actions that glaringly contradict well-established scientific evidence and science-based practices.

A recent example is a ridiculous EU ruling on the usage of scientific evidence in courts.[7] It postulates that in the absence of a scientific consensus on a given topic, the court may now use lesser standards of evidence to make a decision, as opposed to dismissing the case on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

The reaction from the skeptical movement was customary: several podcasts have reported on the ruling and discussed how wrong it is - none of the skeptical organizations actually tried to do something about it. In other words, the skeptical community has discussed it internally, but failed to attempt to change the state of things in the outside world. I am not aware of even a modest street protest initiated by any of the EU skeptical organizations.

This impotence stands in stark contrast to many of the other movements, which actively litigate, lobby and protest laws and court decisions they disagree with. While it is understandable that activism might be impossible in non-democratic countries, the US and the EU skeptics demonstrate a surprising lack of initiative in this regard.

Again, the opposing side - pseudo-scientific movements and fringe religious groups - seem to be much better at communicating their beliefs and staging local events. I have recently observed an anti-science booth at a busy Berlin square. It was there for days, with activists luring passers-by in and handing out leaflets.

I am yet to see a skeptical initiative of that sort on a large scale. Isolated cases exist, like activities of the Good Thinking Society in the UK, but not as something skeptical organizations commonly do. Even these simple social activities are somehow out of scope of a typical skeptical group agenda.

The Wikipedia article on the skeptical movement describes the goals of the movement as "investigating claims made on fringe topics and determining if they are supported by empirical research and are reproducible".[1] In real life this often translates into the investigation of a special group of actors, such as psychics and faith healers. Many skeptical groups consider this to be their primary goal and the primary activism route.

While a lot of resources seem to be allocated to this kind of activity, skeptical organizations don't seem to be very keen on quantifying the effectiveness of their work. When looking at notable cases, this kind of activism seems to have been largely unsuccessful, and demonstrably ineffective as a long-term solution, even in cases when such investigations were apparently triumphant.

I will explore this point in greater detail, as I feel that this activity is a great example of misguided efforts and a failure of critical thinking proponents to apply critical thinking.

One of the big investigations in the history of the modern skeptical movement is the Peter Popoff investigation. While I have no goal of belittling Randi's work on Popoff, I believe that the case is more complicated than is usually presented, and the available data allows for several interpretations.

For example, I could locate no definitive proof that Popoff's downfall in the late 80s was specifically due to Randi's work. The reason why any doubt would be leveled against Randi's claim at all is that other publicized revelations of televangelists have not produced a similar effect. For instance, a CBC Television 2004 special on Benny Hinn had not destroyed the devotion of his following. It is, therefore, not obvious why Popoff's followers would react to Randi's investigation.

In fact, we actually have no data to suggest that Popoff's audience had become disillusioned. All we know is that Popoff went off the air. Good indication that his audience became disillusioned would be data showing that people stopped coming to his events, protests, litigation against him on the grounds of fraud, etc. As far as I know, none of that happened, definitely not on a large enough scale, and instead Popoff's business had succumbed to financial troubles, unrelated to Randi. Of course, the hypothesis that the skeptical investigation did indeed kill Popoff's business is not implausible, but neither is it definitively proven.

Regardless, Popoff has returned in 1998 and continues to operate, earning millions of dollars. It can be argued that this is a direct consequence of skeptical organizations failing to push for regulation. Had skeptical organizations used the occasion to advance a political change, not only would that have had an effect on other televangelists, proclaiming to have supernatural healing powers, it would also have made Popoff's return impossible or very unlikely. Instead, it turned out to be a singular case, with no legislation passed and with Popoff now advertising his "healing products" across the US, Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand.[8] Hundreds, if not thousands of other religious faith healers are operating in the US, mostly unopposed. In 2007, a Senate instigated a probe into several prominent televangelists. So far it has not resulted in any action against them, but the thing to note is that this probe was not brought about by any of the skeptical organizations.

Randi's apparently successful debunking of James Hydrick's claims follows a similar pattern of questionable effectiveness. Hydrick's failure did seem to stop the development of his TV career. During the 80s he was wanted by police on unrelated charges, and in 1989 was finally caught because an off-duty officer saw him discussing psychic powers on the Sally Jessy Raphael, a popular TV talk show at the time. A Tribune article also claims that private security guards who had transported him to the Arkansas jail were afraid that he was using psychic powers to rock the van, and advised jailers not to look him in the eye, saying Hydrick might cast a spell on them.[9] Therefore, it is clear that in the eyes of the general public he was still viewed as a psychic, and had he not been jailed, his activities might have resumed, including a revitalization of his TV appearances.

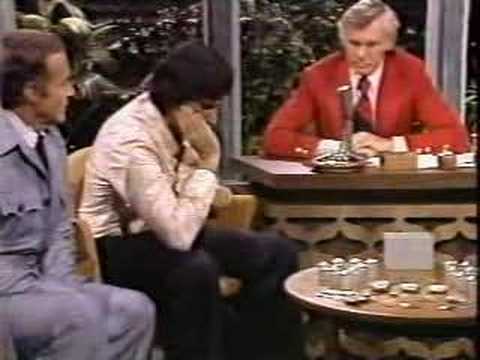

Another notable case, the case of Uri Geller, is well known in the skeptical community. In a way, Uri Geller has defined Randi's career as a skeptic. Randi's involvement in the infamous appearance of Geller on The Tonight Show is an incredibly entertaining and insightful story. What many skeptics might be forgetting, though, is that Randi's struggle against Uri Geller was ultimately unsuccessful. The appearance on The Tonight Show seemed to have the opposite effect. Adam Higginbotham of New York Times writes:

Randi's subsequent book on the matter seemed to have no significant effect either. Geller continues to be successful to this day, living a comfortable celebrity life.

That is not to say that debunking cannot be effective. Done correctly and in suitable circumstances, a proper debunking can discredit a psychic enough to at least take them off the air. After all, Randi was instrumental in thwarting Hydrick's TV career. Why didn't that work with Geller?

The secret is in a way the debunking was performed in each case.

Hydrick was clearly and publicly exposed - not only was he not able to replicate his tricks after the control was added, the fact that the control was there in the first place was evident, and conjuring methods Randi suspected were voiced.

During Geller's appearance on The Tonight Show none of that information was publicly announced. The Geller story continues to be mostly an inside anecdote. The only thing that viewers saw was Geller not being able to demonstrate his feats on the Carson show - quite randomly. They did not know what the reason was, since nobody told them that controls had been added. They did not know what to look out for either, since suspected methods had not been articulated, as they had been in Hydrick's case.

For instance, Randi frequently tells a story of how Geller kept tapping his foot in order to shake the table and see which canisters would shake along with it, thus getting a hint at which ones don't have water. Or that typically Geller would be allowed to inspect the props beforehand, but this time around they made sure he was not allowed anywhere near the props. But none of this was publicly exposed on The Tonight Show.

At the same time, had Carson had the goal of actually exposing Geller, perhaps Geller's TV career in the US would have been over. And one would not have had to be adversarial towards Geller to achieve that. Carson could have started his conversation by saying that a lot of naysayers claim Uri uses methods such as this and this and this to attempt his feats, but "we here decided to put an end to these rumors once and for all, and have prepared props that had been controlled for in this and this and this manner". Such an introduction would have set up an absolutely different paradigm, and would have put Geller into a position of actually proving he is not a fake. It could also have given a hint to other TV shows on how to test Geller, as well as alert viewers to the possibility of trickery and what to look out for.

But none of this was done. And it is therefore not surprising at all that The Tonight Show only bolstered Geller's career. I would even claim that the average viewer was unlikely to see this as an exposé at all. It was an exposé only to Randi, Carson and, perhaps, to some of The Tonight Show crew.

In general, fundamental differences between Hydrick and Geller make it easier to definitively expose the former, but not the latter.

Hydrick purported to possess more or less classic telekinesis - the moving of light objects with the power of the mind. In other words, all very direct effects. The more direct the effect is, the easier it is to add controls and to pinpoint the exact method. Also, direct effects don't allow for too much space to improvise: there are only so many ways to convincingly demonstrate telekinesis.

Geller, on the other hand, mostly claimed to be able to do indirect effects, such as mind reading and seeing through obstacles. These are much more difficult to analyze, as methods will vary depending on the situation. A well-trained and experienced magician would be able to think on his feet and use a plethora of methods to obtain the necessary information. Or even turn the trick around, so that if the initial claim fails, some other surprising effect occurs - a time-honored maneuver that magicians would resort to if asked to repeat a trick. And this seems to be one of the things that happened during Geller's SRI experiments.[11][12]

As a result, it is not always easy to pinpoint the exact method Geller uses. Not only could the methods be improvised, not only would television editing inadvertently hide clues, but a lot of work could be done pre-show, outside of cameras' reach. Therefore, typical debunking of Geller's supernatural claims would rarely involve exact replications of his mind reading abilities.

Additionally, magicians are less resistant towards revealing simple tricks, like appearing to move a pencil. Mind reading, on the other hand, is a modern form of conjuring, and a lot of magicians, including Randi, would be reluctant to reveal the secrets, since many of the methods used by Geller are actually used by professional conjurers. When replicating Geller's feats, Randi never explains how he does it. And to the viewer it is as mysterious as any of the Geller's demonstrations.

But one might also argue that replication is conceptually not a debunking and, thus, not so convincing. That the same effect could be achieved with conjuring does not demonstrate that Geller is a fraud.

The failure of the Million Dollar Challenge

Another initiative, the Million Dollar Challenge, was based entirely on the assumption that debunking is an effective way to change minds. But there is little evidence that the Challenge was actually instrumental at significantly influencing the public opinion on matters of the supernatural. Instead, what we see is continuing deep interest towards the mystical, and dozens of successful psychic careers, which have persisted in the face of all the debunking, such as those of John Edward, James Van Praagh and Sylvia Browne.

Also, the initial purpose of the Challenge was to attract high profile personalities for testing, but that never actually happened. Instead, organizers of the Challenge had to deal with applications from random people, while being ignored by the psychics they were really interested in confronting. The general public did not seem to be interested in applications from unknown applicants either, and testing for the Challenge never became a high profile event.

In my view the Million Dollar Challenge suffers from a number of conceptual problems that have sealed its fate.

For one, it risks too large a sum of money to be believable. The public is likely to think the game is rigged. This circumstance nullifies the effect of high profile psychics refusing the Challenge - if the public thinks the test could be rigged, they would sympathize with refusals. Previous incarnations of the Challenge were more convincing, when the prize money did not exceed $10k.

Second, the results of those tests are not obvious. Even most skeptics won't have a hands-on understanding of statistical significance. For the public the result must be very unconvincing, even if no foul play is suspected. For example, the testing of Fei Wang in 2014 concluded after only two attempts! The reasoning was mathematically sound - Wang could have claimed the million dollars if 8 out of 9 attempts had been successful. But statistics are counterintuitive, and if the purpose of the Challenge was to move the needle of the public opinion, requiring such a high rate of success and then going through with only two attempts is predictably unconvincing - even if mathematically correct.

All of this shows that debunking is not a straightforward activity, and its effects are both limited and greatly dependent on a whole set of factors, from the claim being made to the surroundings in which purported miracles are performed. For a whole class of claims, debunking should perhaps be avoided.

It also shows that the skeptical movement got too entangled in its own subculture. Endless re-tellings of famous debunkings at skeptical conventions, young skeptical groups trying to emulate Randi's Million Dollar Challenge, frequently making the same mistakes in the process - none of this is critically evaluated for efficiency and ability to produce real change.

My goal is not to say that the skeptical movement adds no value to the world. Uniting like-minded people, letting skeptics know that they are not alone has changed the lives of many people. The only thing I am saying is that the skeptical movement is not a movement that produces real change in the non-skeptical world, i.e. it is not an activism phenomenon.

Skeptical organizations are mostly focused on in-group activities, and can be more accurately characterized as think tanks rather than activist groups. Their agenda continues to be largely unknown to the public, and their vision of the world is mostly unfulfilled.

In the public eye, even the term "skeptic" has not been established to any degree of clarity, and although most activist terms, like a "feminist", are prone to misinterpretation and stereotyping, what a "skeptic" stands for is even less clear to the general public, whereas the term "scientific skepticism" is often understood as "being distrustful of science" - an exact opposite of what it is meant to convey.

At the same time, if one wants to change the world, the skeptical movement has a wide variety of options, from simple political action, such as protests and city events, to lobbying, litigation and becoming a vocal part of the political conversation.

A number of skeptical initiatives are an exception to the rule and are outward-looking. An illustrious example is Susan Gerbic's "Guerrilla Skepticism on Wikipedia" project.[13] It is a perfect example of activism that is focused on non-skeptic audiences. Thanks to Wikipedia's reporting tools, the reach of GSoW is also quantifiable.

Activism is hard and often messy work. As soon as an activist group begins to push for its agenda in the real world, controversies are likely to erupt. Skeptics know what it is like to receive push back from the paranormal community. This might be nothing compared to the backlash they might receive if they actually begin to engage in political action.

But this is the price of changing the world. If skeptics want change, they have to actually start working for it.

4. Common objections and additional notes

4.1 I don’t want to change the world. I want to inspire the world to change itself.

This is a relatively common sentiment.

The short answer is that inspiring the world to change itself falls under the definition of changing the world. It still requires a strategy and an execution of this strategy, as said inspiration must somehow be produced and then delivered to the public.

If we dig slightly deeper, the underlying logic of the objection requires us to discern two methods of activism:

a. forcing your worldview via political action

b. changing the public opinion (with the expectation that political action would naturally follow)

Any activism typically utilizes both, but within the community some people would be more comfortable with the former and some - with the latter.

It is important to understand that the core argument is not made irrelevant by subscribing to the strategy of changing the public opinion. Even if one would rather convince the public of the value of skepticism, it is clear that there should be a coherent outward looking plan. Some of the more effective routes, like inclusion of critical thinking into public schools, may make political action unavoidable.

But even if one instead opts for a strictly non-political agenda, like the production of media content geared towards the general public, clearly today this strategy is not pursued with any noticeable rigor. As stated earlier, audiences of skeptical organizations are mostly like-minded people, and there seems to be little effort in reaching out beyond this closed circle.

Therefore, consistent adherence to the idea of inspiring real change must mean focus on skeptical outreach.

4.2 Political action risks introducing unforeseen harm.

When talking about isolated cases, such an approach is prudent. Colloquially, this advice is usually worded as "pick your battles". Presented as an overarching philosophy, however, it raises an objection of being unjustifiably cautious.

After all, any action has a risk of introducing harm, and it is always a question of weighing risk versus benefit. In case of skepticism, while a lot of questions raised are of a philosophical, abstract nature, quite a number of issues are questions of life and death, like vaccination and other questions of public health. The potential benefits of fixing the problems in these areas are enormous.

If skeptics truly believe that their methods and worldview are accurate and ultimately beneficial for everyone, choosing not to act because an unforeseen problem might occur is irrational. Clearly, while unforeseen harm is always part of the equation, anticipated benefit is overwhelming.

Additionally, there are ways to cope with arising difficulties. Not all harm is unforeseen, and not all unforeseen harm is irreparable. If the cause is important, it might be reasonable to act - and face possible complications as they arise.

This is true for all social movements. When we decide to fight for human rights, we are aware that even the best of intentions might create unforeseen suffering. But we believe the cause to be so far-reaching, and potential benefit so overwhelming, that we prefer to deal with unforeseen harm when it presents itself. We don't stay idle simply because there is a possibility of a problem.

4.3 There is no single goal in skepticism, that's why the results are so few.

Having multiple goals doesn't mean having no results. If the goals are so vastly different so as to render any action impossible - then we would be looking at a dysfunctional movement, for sure.

But there is no evidence that skeptics are not united by goals, common enough for concerted action to be possible. The vast majority of skeptics are likely to agree that anti-vax movements are a danger to public health, that critical thinking and how science works should somehow be introduced into basic education, that medicine should be evidence-based, that taxpayers' money should not be wasted on research of implausible and already refuted medical practices, etc.

This objection could also be read to mean that not all people, identifying as skeptics, are looking to become activists. But this is true for any social movement. Not all people who identify as feminists will want to put an effort into actual activism. Obviously, the skeptical movement has people who are eager to change the world.

4.4 The Catholic church took hundreds of years to establish itself. The skeptical movement is mere 40 years old.

The Catholic church is not a social movement. Initially, it was a cult that fought for dominance in a deeply religious society, at a very different time, under very different circumstances. The correct comparison would be to compare the skeptical movement to other contemporary social movements - feminism, environmentalism, etc. And it is clear from their examples that 4 decades is quite enough for at least some results.

But there is a more fundamental response to this objection. The article does not simply claim that the skeptical movement has no tangible results. It additionally claims that most of the time there is not even an effort made towards trying to achieve tangible results.

It's not like the skeptical movement routinely tries to oppose anti-scientific laws and fails, or tries to create content for the general public - but it doesn't catch on. Most of the time no such initiatives are even undertaken.

4.5 Greenpeace is a very unpopular organization among skeptics. How can you compare us to Greenpeace?

I am not. Comparing a movement to an organization would be committing a category error. Instead, I am comparing skeptical organizations to other organizations - like Greenpeace. The views of Greenpeace in this context are irrelevant, Greenpeace is simply an example of an activist group that focuses on producing change.

4.6 Conferences don't make change happen, they are the way we network to produce change.

My argument is not that conferences should make change happen, but rather that very significant resources are thrown at conferences. The decision to outline their statistics is done in the anticipation of an argument that conferences in and of themselves are educational events that are visibly changing the world. Available data demonstrates that they are not.

4.7 There is an opinion that the skeptical movement is actually doing a terrible job at maintaining a robust community.

I agree. The fact that after 40 years even larger skeptical events cannot break the ceiling of a 1,000 attendees demonstrates a lack of significant growth. Local skeptical groups tend to be understaffed.

However, the topic of the article was to see how good the skeptical community is at changing the world. Compared to this goal, the activities to build a community are definitely more successful.

A 2023 note: one thing that I forgot to add to this analysis, but which was part of my thinking at the time was that skeptical activists tend to focus on a very narrow set of topics. A lot of those topics, I wanted to argue, are fairly obscure and are mostly relevant to obscure groups. Whereas there are many everyday topics that are crying out for a proper critical thinking approach. For example, the practices of hiring - and not the Myers-Briggs that we skeptics immediately think to - but the more benign-sounding, but problematic concepts such as behavioral interviews, that are falsely considered to be bias-free and objective and dominate the corporate world. Many more examples can be brought up.

However, I got a bit too caught up analyzing the One Million Dollar challenge, which I think is important analysis, don't get me wrong. But I completely forgot to write about this point. I still think it's valid and it became very clear to me once I found myself outside the skeptical bubble. Why was I so squarely focused on psychics as an activist, but not on other areas of life? Critical thinking is lacking in all of them, with significant impact on everyone's life.

2. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry

7. Terrible Decision from the Court of Justice of the European Union

8. Peter Popoff

9. 1980s TV 'psychic' and sex offender wants to be freed from mental hospital

10. The Unbelievable Skepticism of the Amazing Randi

12. Kurtz, Paul. (1985). A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology. Prometheus Books. p. 213. ISBN 0-87975-300-5

"Skeptics have criticized the test for lacking stringent controls. They have pointed out that the pictures drawn by Geller did not match what they were supposed to correspond to but appeared, rather, to be responses to verbal cues. What constituted a “hit” is open to dispute. The conditions under which the experiments were conducted were extremely loose, even chaotic at times. The sealed room in which Uri was placed had an aperture from which he could have peeked out, and his confederate Shipi was in and about the laboratory and could have conveyed signals to him. The same was true in another test of clairvoyance, where Geller passed twice but surprisingly guessed eight out of ten times the top face of a die that was placed in a closed metal box. The probability of this happening by chance alone was, we are told, one in a million. Critics maintained that the protocol of this experiment was, again, poorly designed, that Geller could have peeked into the box, and that dozens of other tests from which there were no positive results were not reported."

13. Guerrilla Skepticism on Wikipedia